Faces of Land Policy

Friedrich August von Hayek

The Austrian economist F.A. Hayek (1899–1992) hated planning. In his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, he defined planning in a way that many planners presumably find acceptable. Under this definition, planning connects the past, the presence, and the future by solving common problems “rationally” and with “foresight”. This definition can be misunderstood as saying that planners can escape social, economic, ecological, or political mortality (and Hayek feared that planners would give in to the temptations of collectivism and central planning).

The picture shows a memento mori (= remember your mortality!) in the City of Höxter, North Rhine-Westphalia.

Martin Luther King Jr.

In A Letter from a Birmingham Jail (1963), civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968), explained why looking for everyday injustice is more important than the quest for ideal justice. The quote presents an ecological definition of injustice. Like pollutants in the air or water, through environmental cycles, find their way into human organs, injustice has the toxic power to contaminate social and political relationships even quite distant from the source of injustice.

The sculpture Macht zu Lande (Power over Land) by Edmund von Hellmer decorates the Hofburg, the former Habsburg castle in Vienna-Central City. Depending on the viewer’s perspective, the face of the giant (a son of the Earth) appears to be devious, angry, vulnerable, violent, or frightened.

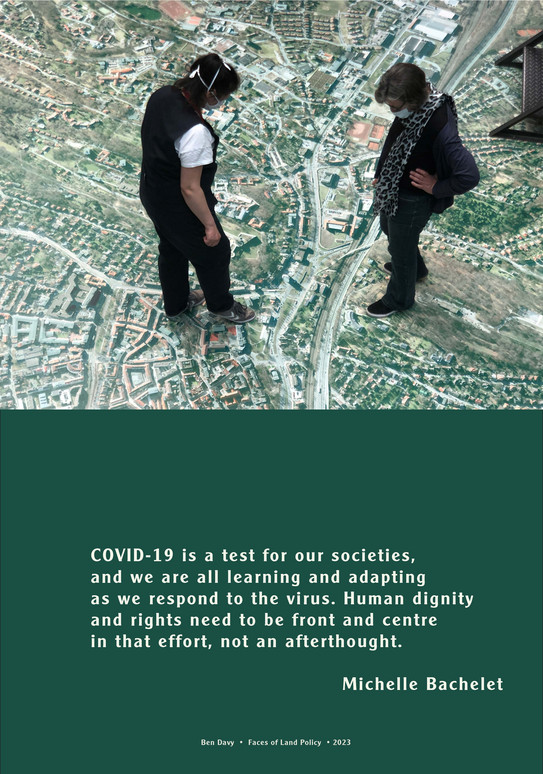

Michelle Bachelet

Verónica Michelle Bachelet Jeria (b. 1951), a Chilean surgeon, was President of Chile from 2006–2010 and 2014–2018. From 2018 through 2022, Bachelet served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Her call to respect and protect human dignity and human rights in the struggle against COVID19 was widely ignored.

Visitors entering the Bielefeld museum of history admire an aerial photograph of the city located in the East of North Rhine-Westfalia. Dressed for the occasion (summer 2020), they are wearing face coverings and keep social distance.

Aldo Leopold

In the final chapter of A Sand County Almanac (1949), environmentalist Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) presented his land ethic. The land ethic was an early (modern) version of biocentric environmental policy (not the human species, but Nature is its focus). Leopold regarded humans not as conquerors, but as citizens of the land community. In particular, he was critical of reducing the value of land to its economic exchange value and of ignoring the existence value of land. Because of the heavy weight he put on environmental values, Leopold was accused of “environmental fascism” by Tom Regan, an advocate for animal rights.

In the spring of 2021, during the third wave, this bee was not impressed by lockdown commands. She still kept social distance, though.

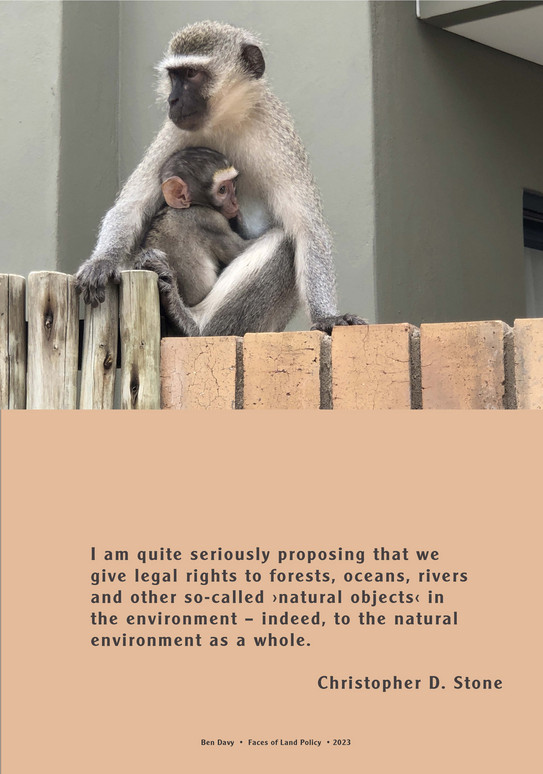

Christopher D. Stone

In 1972, legal historian Christopher D. Stone (1937–2021) asked a question which guided 50 years of debate: “Should trees have standing?” (= Should trees have legal personhood and rights?) Stone answered in the affirmative, yet the environmental rights discourses have branched out: animal rights and dignity, land use ethics, rights of nature, tree rights, rights of rivers and oceans, ecological personhood, guardianship, and many more. Some of these discourses contradict each other directly (e.g., Leopold’s land ethic and Stone’s animal rights).

Animal rights often draw from similarities between human and non-human animals. It is easy to detect a human approach to motherhood in the photograph of monkeys in Kruger National Park. But what about other animals – venomous snakes and spiders, man-eating sharks, or SARS-CoV2?

Martha C. Nussbaum

Philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum (b. 1947) called Justice for Animals (2022) “our common responsibility”. Nussbaum regarded humans as (illegitimate) dominators of animals. Elaborating on her earlier capabilities approach, she explained what needed to be done to restore the imbalance between human demands to use animals and the moral right of animals to exist.

In a world where millions of children go hungry to bed each night and countries worldwide invest billions in an obscene arms race, the deliberation of animal rights may seem frivolous. Since “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” (King), the trouble for animals cannot be considered separately from other trouble. The poisoned tree bears many different fruits.

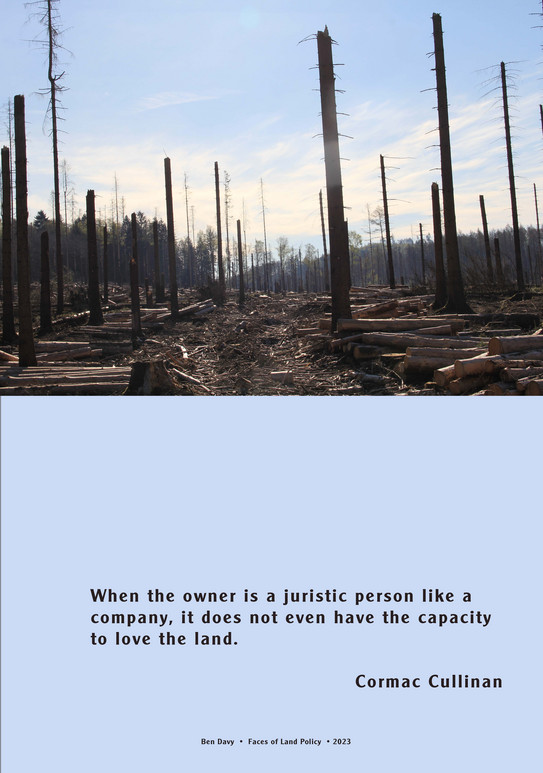

Cormac Cullinan

South African lawyer Cormac Cullinan wrote the book Wild Law – A Manifesto for Earth Justice (2002). The poster selects a quote from Wild Law that refers to the complex relationship between property rights and corporations. Legal and political discourses predominantly treat the property rights of natural and legal persons equally. This is a huge mistake. Whereas property of natural persons is a guarantee of individual liberty, the property of companies is not a right but a social function (Duguit). Cullinan expressed the huge difference rather cleverly: Companies cannot love the land!

The climate crisis always is exacerbated by the crisis of capital (that cannot love). Vast tracts of forest in North Rhine-Westphalia have been destroyed by a combination of arid summers, bark beetle infestation, and monoculture.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) examined the German ideology, a treatise that was published posthumously. The quote confirms the strategic significance of the “ideas of the ruling class”. It calls into question, however, how materialistic the theory of historic materialism really was supposed to be. How materialistic is a “ruling intellectual force”?

The laundry surely is materialistic. It receives its aesthetic flamboyance through mere air that – as a forceful gale – shapes a gesture of resilience in the face of the third COVID19 wave. Air is lofty and soon will be gone. The air determines the mind: Die Luft bestimmt das Bewußtsein.

Léon Duguit

What blasphemy! Léon Duguit (1859–1928), an eminent professor of constitutional law from the University of Bordeaux, rejected the libertarian concept of private property as an absolute right of the landowner to exclude everybody else from the use of land. Rather, Duguit considered property as a social function. Conservative property theorists rejected Duguit as forceful as communist legal theorists.

I took the picture of the prominent crucifix and the tiny penis in the Friedrichwerdersche Church in Berlin. Designed by Friedrich Carl Schinkel (1781–1841), the church after its profanation today houses a fascinating exhibition of 19th century sculptures.

John Locke

One root of the idea of private property as an absolute right was the appropriation theory proposed by John Locke (1632–1704). Locke’s property theory occupied vast parts of the second volume of Two Treatises of Government (1689). Its agrarian approach to property acquisition appeared rather romantic: A farmer drenched in his own sweat toils day in and day out to put food on the table (incidentally, he is also rewarded by the right to appropriate the land as his property). Locke’s bucolic view does not comment on slave ownership, plantation economies, King Cotton, exploitation, and early capitalism.

In times of energy scarcity, the use of and property in air suddenly becomes vital for the survival of the carbon-deprived extraction capitalists. Will air ultimately also be parceled out and propertized?

Auguste Comte

One of Duguit’s inspirations, the French mathematician and sociologist Auguste Comte (1798–1857) published Système de Politique Positive in several volumes. Volume 1 (1875) explained how property rights have changed their meaning. During times of tyranny and feudalism, citizens needed their property protected from capricious government intervention. In modern times (such as Comte’s 19th century), property did not need protection but promotion as a tool of social cooperation. Comte feared that economic and social progress would be hampered by egoistic owners, who were unwilling to listen to the voice of the public best.

This sculpture in the baroque garden Großsedlitz in Saxony reminds visitors of the cruel view held by past generations that the rape of one’s wife, daughter, or maid equals the free use of one’s property.

T.H. Marshall

T.H. (Thomas Humphrey) Marshall (1893–1981) invented “social citizenship” as adjacent to civil and political citizenship. Even if the government was not able to turn every man into a gentleman, they would be responsible for providing everybody with a social modicum. In Citizenship and Social Class (1950), Marshall compared social politics and the welfare state with town planning. The purpose of town planning was not, Marshall claimed, that classes be abandoned, but that each class would find housing suitable to their needs and income. Marshall regarded town planning as the “architect of social inequality”!

The City of Vienna has often found amiable solutions to dire problems of social inequality. None of them can be seen in the picture that shows imperial architecture in Vienna’s town center.